Programming drums are one of those things you are either for or against. It’s a topic that creates a rift in the technical music industry and can lead to some pointless arguments. My approach to it is this: If it sounds good, who cares!? Whether you’re a budding 1980s synth-pop musician rocking out on the LinnDrum, a true Hip-Hop head working with vinyl and an MPC, or simply a guitarist who can’t find a band, programming drums that sound realistic is going to be pivotal. Previously, we’ve discussed ways to make MIDI sound realistic. Today, we look to break down some of the finer points of programming drums. Let’s discuss the nuances that can make your drums trick even the best of percussionists.

Table of Contents

- Varying Up Velocity

- Repetition, Repetition, Repetition

- Getting Out Of Gridlock

- But What If I’m Too Far Off The Grid?

- A Few Words On Tempo

- Layering Up Sounds

- A Few Easy Automation Tricks When Programming Drums

- TL;DR

Varying Up Velocity

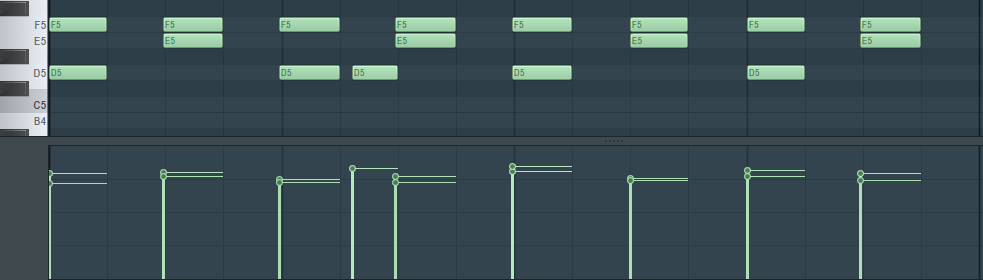

Velocity adjustments are as important as timing. In fact, they may be even more important because, sonically, minor velocity changes are much easier to detect. Equally, dynamics play a huge part in almost all music. As such, getting specific with your velocity is going to be a must for realistic-sounding drums. As you may or may not be aware, MIDI data ranges from a value of 0-127. In the case of velocity, 0 is silence and 127 is maximum volume. This means you’ve got quite a high level of precision available to you when programming velocity.

When thinking about velocity, try to imagine a real drummer playing the part. Just as they won’t hit every note at exactly the same time, they won’t hit it with the same intensity. Whether this is on purpose or simply a lack of robotic precision, it’s a ubiquitous trait of drum patterns. Here, you can use humanization or randomization features to adjust velocity changes within a percentage range to add variation to static drum patterns. When doing this, a percentile variation of about 10-15% is plenty. Equally, delving into the patterns and making small adjustments to find the pockets in the rhythm of the song will really help to bring your drums to life. Manually syncing up your kick, snare, and bass line can create a far more natural-sounding low-end rhythm section.

Repetition, Repetition, Repetition

Now that you’ve got your drum patterns programmed in with a great variety of timing and velocity, you need to look at things in terms of the bigger picture. It’s great to have a really unique and dynamic 16-bar loop, but if it repeats over and over for the next 3 minutes, it’ll quickly lose its charm. This is simply fixed by making sure you have variations on your basic pattern.

Much like any form of songwriting, we start with a basic progression and build upon it from there. When I’m working on a Hip-Hop track, I’ll routinely start by programming drums with a strong groove that can hold up the majority of the song. Once that’s done, I’ll create 4-8 variations on this pattern that I can drop into places that feel like they need a bit of a change. These may be as simple as having an extra kick drum on the 2 or as complex as using mutes and breakdowns as a technique for music transitions. Taking the time to make these small changes helps to keep your music fresh and generally more realistic.

Getting Out Of Gridlock

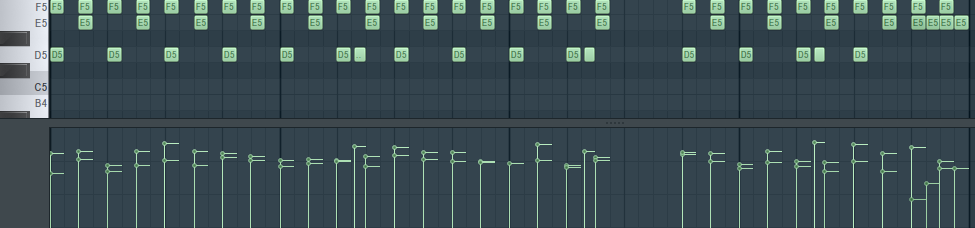

One of the biggest and most obvious signs of programmed drums is rigidity. A drumbeat that lacks variety will inevitably lack interest. Think about how mundane it is to repeat the same task over and over. This translates in the same way when it comes to programming drums. Learning to groove like a drummer and getting outside the grid lines will have a massive impact on your music.

The next time you are programming drums, think about the variety that songs with real drummers have. It’s practically impossible for someone, no matter how good they are, to hit the exact same mark in every bar. As such, moving your MIDI data slightly off the grid can help to emulate this humanization. By adjusting perfected grid timings by up to 20%, we can generate some uniqueness in our grooves. Many DAWs will have a humanize or randomize function that allows you to do this. Simply program your entire drum track, then grab all of the data and randomize it by a fixed percentage. By doing this with the data for an entire song as opposed to just a four or eight-bar loop, we create unique variations throughout the entire production. This is far more likely to replicate the natural abilities of a drummer.

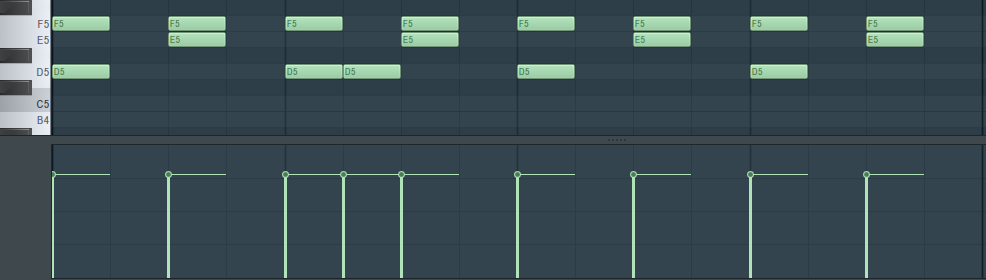

But What If I’m Too Far Off The Grid?

Now, for those of you who like to get a bit more hands-on with hardware, the opposite tends to apply. Playing your drums with a drum pad or MIDI keyboard is a great way to add some character. However, hitting it too hard with quantization afterward makes all that work practically redundant. After all, it’s not supposed to be a metronome! Instead, make sure you’re loose with your quantization and only allow for around 80% correction. This way, you will still achieve an ever-changing pattern, but it won’t sound out of time. Equally, pulling up the MIDI data and making manual adjustments can increase the convincingness of your programmed drums. This usually comes down to the ear, but making slight alterations in timing where necessary can really help to tighten up the rhythm of a track. This is especially true when programming drums against audio files played by real musicians.

A Few Words On Tempo

If you’re working on fully electronic music, the chances are you’re going to want a rigidly consistent pace. It’s uncommon to listen to dance music or Hip-Hop that has tempo shifts. It just doesn’t suit the nature and purpose of the music. However, if you’re looking to work in a genre that is typically more acoustic, tempo variations can be another great trick to improving the sound of programmed drums.

If you’ve ever been to a live concert for a band you know inside out, you’ve probably noticed that the music always feels a little faster when you’re at the show. This is generally due to the energy that a live performance provides. Most bands will be somewhere between 1-3 BPM faster in a live setting than they are on a record. This speed increase can also be felt in some records where the level of energy is similarly increased. Leading into choruses or breakdowns, it’s not uncommon to see the tempo ramped up by a tiny amount. This is by no means a very common technique, but it’s definitely a useful one to have in your toolkit should you require a little more energy. It’s subtle enough that you don’t notice it but big enough to provide that extra push.

In terms of programming electronic drums, tempo automation can be a great help. This is even truer when the drums are being programmed as a rhythm guide for real recordings. Being able to push the band slightly up in speed keeps control of these tempo changes and ensures things are tight on every instrument. Even more importantly, setting a fixed tempo to work to that is defined by your programming prevents any unwanted rushing or dragging when recording. This saves hours in post-production.

Layering Up Sounds

Another useful tip for keeping things interesting is layering. This is a concept you can approach in two ways. You can either use unusual sounds that appear in your pattern variations to create unique sections, or you can use layering throughout to add a sense of realness to your track. It’s hugely common for those of us who like to work with breaks to use them as the backbone of a beat and then layer them up with one-shot samples. By doing so, you can replicate the authentic groove of a real recording. You can’t get much more realistic than that.

This isn’t a technique that is solely exclusive to anyone working with breaks either. These days, places like Splice offer such a variety of samples that you are bound to be able to find a real drum beat that fits your work. Being able to grab a real recording and then chop, rearrange, and build upon it is not only hugely realistic, but it’s a massive time saver. The next time you need to program in some drums, try doing so by building off of a real groove. Even if you choose not to keep that groove in the track, the drums you’ve programmed over the top are going to have a much greater degree of realism than they would if they had just sat on the grid.

A Few Easy Automation Tricks When Programming Drums

As a final note, there are a couple of neat little tricks you can implement with automation or with free VST plugins that can improve your drums. The first of these is using an auto-pan or panning automation on your cymbals. Most drummers have at least two cymbals and quite often more than that. By utilizing panning or auto panning, you can vary up their position in the stereo field as if you had ten cymbals in your overheads. It’s a subtle adjustment but one that helps to improve the character of your drums and make better use of the stereo field.

Another handy little trick requires a filter that you can control with an LFO. I like to use WOW by Sugarbytes for this as its filter is controllable via an LFO or step sequencer. By applying this plugin to your hi-hats or percussive elements, you can simulate tonal contrast in a singular sample. Let’s say you’ve programmed your hi-hats into a straight 4/4 pattern using one hi-hat sample that triggers repeatedly. This is going to sound out of place because when we hit real hi-hats, the tone of each hit changes due to the remaining vibrations from the previous hit. This, coupled with a drummer’s groove, typically results in one bright hit followed by one slightly duller hit. By using a low pass filter controlled by an LFO, we can automate it to give us one bright hit with the filter fully open, followed by one duller hit with the filter slightly closed. Used sensibly, this can provide some great movement in your grooves.

TL;DR

There are plenty of things we can do to improve programmed drums. Delving into the timing and velocity of your MIDI data is going to be key to humanizing your patterns. Creating variations on your patterns helps to keep things interesting as the song moves on. Layering can be a great way to add a sense of realism to your work. It also allows you to copy and build upon real drummers’ grooves. Finally, automation is your friend. Using it to create subtle changes helps to improve the groove and saves you a lot of time in editing.

About the Author

Tim Dunphy

Audio Engineer and Specialized Content WriterOver 10 years experience working in the audio business. Everything from coiling up XLRs to mastering albums. I'm a self-made man and I keep my assets in Bitcoin. What more is there to know!?

Leave a comment

Log in to comment