Mixing in mono is an often-overlooked technique that significantly impacts the tonal balance, phase coherence, and overall clarity of your mixes. While stereo is the standard for modern music, learning to collapse your mix to a single channel will reveal hidden problems and ensure your music sounds great on a wide variety of playback systems. Let’s explore what mono mixing is, why it matters, when to use it, and how to apply it practically.

Table of Contents

- What is Mono Mixing?

- Why Mix in Mono?

- When to Use Mono Mixing

- How to Mix in Mono

- Considerations when Mixing in Mono

- Conclusion

What is Mono Mixing?

Mono mixing means creating your audio mix in monaural sound – i.e. combining all audio tracks into one single channel output, instead of the usual two channels of stereo. In a mono mix, the left and right speakers play identical audio, resulting in a single centered image of the sound. By contrast, a stereo mix has two different channels (left and right), which allows sounds to be panned and spread across the stereo field. According to audio engineering basics, mixing is the process of blending multitrack recordings into a final product that can be mono or stereo (or surround). In other words, stereo is now the norm, but mono is an equally valid (if less common) format for a final mix.

In simple terms: Mono = one sound source; Stereo = two sound sources. If you play a mono song through a pair of speakers or headphones, both ears get the same audio signal. There’s no sense of width or direction – everything feels like it’s coming from a single point. Play a stereo song, and you’ll hear some instruments toward the left, some toward the right, and a sense of space in the mix. For example, a stereo mix might have the guitar panned a bit right and the keyboard a bit left, whereas a mono mix would have both guitar and keyboard coming straight down the center.

Why Mix in Mono?

Mixing in mono might feel like handicapping yourself (since you’re giving up all those cool stereo panning tricks), but there are two big reasons why it’s so powerful: tonal balance and phase coherence. By forcing all your sounds into one channel, you really hear how they stack up on top of each other. This makes it easier to spot frequency imbalances and phase issues that you might miss in stereo. Let’s break down these benefits:

Tonal Balance Focus

When you listen in mono, you can immediately tell if your mix’s frequency balance is off. Because every instrument is competing for the same center space, any boomy buildup or harsh frequency will stick out like a sore thumb. You can’t rely on panning to separate a muddy bass from a thick guitar – you have to use EQ, compression, and volume to get each element sitting right. The result is often a mix with better clarity and balance across the frequency spectrum.

No hiding behind panning

In stereo, you might pan a synth left and a guitar right to make them both audible even if they share similar frequencies. In mono, they’ll sit right on top of each other. If the combination sounds cluttered, you know you need to adjust levels or EQ. This forces you to carve out space for each instrument’s critical frequencies (for example, cutting some mids from the guitar to let the synth through, or vice versa) until the mix sounds clear.

Better overall EQ decisions

Mixing in mono encourages bolder EQ moves to fix tonal clashes. You’ll likely find yourself taming an overly bright cymbal or reducing muddiness in the low-mids more readily, because you can immediately hear the benefit when everything is summed together. In stereo, those problems might be masked by separation; in mono, there’s nowhere for an ugly frequency to hide.

Balanced levels

Similarly, mono mixing forces you to get the volume balance of tracks just right. If a background vocal is too loud or a rhythm guitar too quiet, it will be obvious in mono. You can set relative levels such that nothing important disappears and nothing unnecessary overpowers. Once you pan things out in stereo later, that level balance holds and each element remains audible and well-balanced. Many engineers find that if the mix’s levels are balanced in mono, the mix will only improve in stereo.

In fact, it’s often said that “mixes that sound good in mono will usually sound great in stereo.” This isn’t just a cliché – it’s true more often than not. By nailing the tonal balance in mono first, you set yourself up for a mix that has clarity and punch when expanded to full stereo width. Think of mono as a stress-test for your mix’s foundation: if the foundation is solid, adding stereo effects and panning will be icing on the cake.

Phase Coherence

Phase issues occur when two similar signals arrive with slightly different timing or polarity, causing cancellation when summed. In stereo, out-of-phase elements can appear wide, but in mono they might vanish or sound thin.

Common Phase Problems

- Stereo widening plugins sometimes invert phase between left and right.

- Drum mic bleed or multiple mics on the same source can cause cancellations.

- Bass or sub frequencies can hollow out if they’re stereo instead of centered.

By checking in mono, you can identify and fix these phase issues before finalizing your mix.

When to Use Mono Mixing

Should you stay in mono the entire time? Not necessarily, but there are strategic points where mono mixing is most beneficial.

Early Stages

Setting initial levels in mono prevents any illusions created by stereo panning. You’ll focus on making instruments fit together frequency-wise, ensuring no single track dominates.

Periodic Checks

Even if you prefer to work mostly in stereo, toggle mono on and off throughout the mix. This reveals hidden masking or imbalances, allowing you to fix them.

Final Mix Checks

Before exporting or mastering, do a full listen in mono. Make sure no essential elements disappear. This step helps your music translate well to car speakers, small radios, and club systems (often effectively mono).

How to Mix in Mono

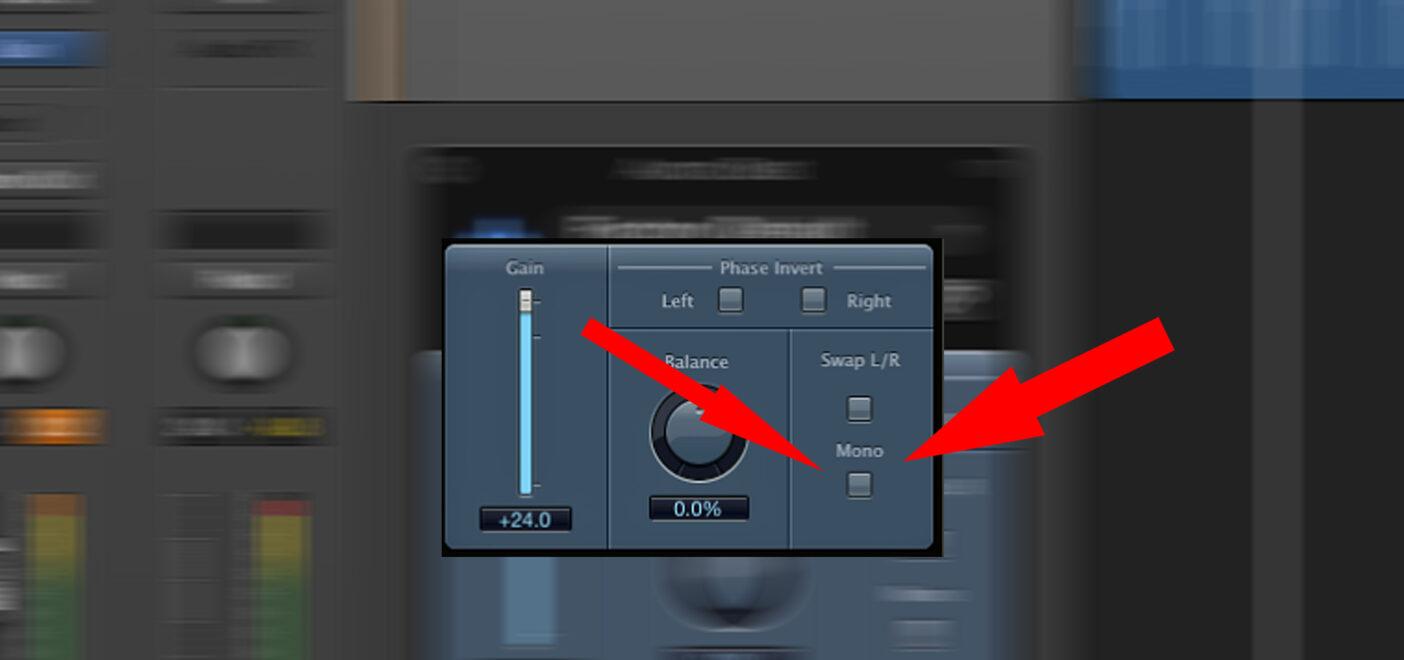

Mixing in mono involves listening to the entire track through a single channel, which can be achieved via a dedicated mono summing button on hardware or a plugin within the DAW. This approach clarifies issues like phase cancellation and imbalanced panning that can be hidden in stereo. By collapsing everything into one channel, any instruments out of phase will partially or completely disappear, making it easier to adjust their levels or re-check their polarity. Plugins like a DAW’s built-in utility or third-party tools can sum the master bus to mono; in a pinch, one could pan every track to the center, though that can be cumbersome for large sessions.

A popular approach is to use a single speaker, such as an Avantone MixCube, placed in front of the engineer. This method ensures no stereo effect is present, emphasizing important mix elements. If the mix holds up under this setup, it’s likely to translate well to headphones, smartphones, and stereo systems. Engineers also rely on headphones for mono referencing by routing the signal through a mono bus. While this still sends identical signals to the left and right ear, it highlights any hollow or phasey artifacts that might emerge from improperly aligned stereo tracks.

Aside from summing approaches, visual phase tools like correlation meters help identify potential phase issues by reading negative or zero values that signal trouble in mono. Basic real-world checks, such as playing the mix through a phone speaker or an older car system, further confirm whether essential elements remain prominent when folded down to mono. Ultimately, mixing in mono is a practical strategy for ensuring clear, balanced mixes across diverse playback environments. By focusing on clarity and balance in the simplest listening format, an engineer lays a solid foundation for a polished final product in full stereo.

Considerations when Mixing in Mono

When it comes to mono mixing, there are a few practical points that can make or break your final track. Keeping bass frequencies focused, taming stereo effects, and using mono as a foundational tool are just some of the steps that give you a rock-solid mix. Below, we’ll explore how to handle low-frequency elements, approach stereo processing, and use mono checks without over-compensating.

Bass and Low-Frequency Elements

Because low frequencies are especially vulnerable to phase issues, many producers keep the sub and bass instruments centered. Stereo-processing on these frequencies can cause inconsistencies, so always check in mono to ensure punch remains intact.

Stereo Effects and Widening

Stereo reverb, chorus, and other width-enhancing effects can create beautiful space. However, they’re sometimes achieved by inverting phase between the left and right channels. When you collapse to mono, these effects might become thin or disappear. Testing them in mono helps maintain a balance between stereo excitement and mono compatibility.

Mixing with Mono as a Foundation

Many engineers start a mix entirely in mono. If you can get a solid, balanced mix without panning, adding stereo width later will only enhance the results. Think of mono as a foundation and stereo as the finishing touch.

Avoid Over-Compensation

When you collapse to mono, certain instruments might feel like they lack presence. Sometimes, it’s a genuine problem; other times, it’s just the natural cost of removing stereo width. Avoid over-processing in mono. After you address genuine issues, switch back to stereo to re-check your decisions.

Conclusion

Mixing in mono is a powerful yet straightforward technique that improves your music’s clarity, balance, and phase stability. By focusing on mono at key stages of the mixing process—setting initial levels, performing periodic checks, and doing a final pass before mastering—you ensure your mix translates across any playback scenario. From EDM to rock, hip-hop, and pop, each genre benefits from having a strong mono core. So don’t be fooled by the simplicity of one channel—try it out, and watch your stereo mixes reach new heights of punch and clarity.

Sobre o Autor

Tim Dunphy

Engenheiro de Áudio e Escritor EspecializadoMais de 10 anos de experiência na indústria do áudio. Desde enrolar cabos XLR até masterizar álbuns. Sou um homem feito por mim mesmo e guardo os meus ativos em Bitcoin. O que mais há para saber!?

Deixa um comentário

Entra para comentar