Bass has always been an incredibly important component in records, from older to newer. It keeps the rhythm locked in with the drum beat and kick patterns and provides the anchor on which the rest of the tune can elaborate more freely. In the digital realm, the methods available for efficiently mixing bass have increased alongside the rise of more bass-heavy tracks.

Producing bass has developed over the years, and now we have access to extremely low sub-bass that didn’t exist before. Speakers couldn’t effectively generate sounds that low. Anything below 60Hz is considered sub-bass, which is mostly felt rather than heard, from frequencies ranging from 20Hz to 40Hz. A bass guitar can achieve a pitch as low as 41Hz, and the lowest piano note, the lowest A, is 27.5Hz. There’s a fair bit down there that can’t be easily achieved with acoustic instruments, so techniques for mixing bass have evolved! At least the huge, pumping sub-bass we hear these days is purely a modern phenomenon. If you want to explore the world of bass a little more, check out choosing your first bass guitar.

Bass is challenging to mix properly because it has so much sonic energy when used in music – it’s chunky and loud, but at the same time, because it’s so low, it appears rather quiet to us due to the way the human ear has evolved. Tight, punchy bass will make all the difference when you master it on MasteringBOX. So that’s the dilemma: how do you get punchy, large bass sounds that don’t take up too much headroom or use too much of your song’s energy without issues or distortion?

When mixing bass, check these three steps to help you get the best results.

1. Clear Up Space In The Low Frequencies

Once you start composing and arranging your tune, pay attention to elements of your track that have a lot of bass frequencies lying under around 100Hz. It’s quite surprising how many software instrument patches have really bassy harmonics. Working out what needs low-frequency content and what doesn’t is important when you come to mix your bass. They’ll clash with your actual bass significantly. Samples are the same; there’s often hidden bass that doesn’t sound good and isn’t needed. Many of these sounds that contain hidden bass might be in stereo too, so you’ll have this layer of stereo bass hidden in your track, which can cause all sorts of problems. Get into the routine of cutting the bass using high-pass filters; don’t be worried about cutting too much bass, as your finished mix will thank you for being surgical here (read: Audio Filter Types).

One thing you can try is putting an EQ on your master and low-passing it around 150Hz. What you would ideally like to hear is a clear, clean bass sound that isn’t muddied by other sounds that don’t need low-frequency information. Find those rogue bass tracks and cut them!

2. Make Your Bass Mono

There is some leeway, but when you come to mix bass, your lowest bass should be mono. This is because our ears struggle to position bass. Consider a sharp, crisp hand clap; you can instantly identify if it’s coming from the left or right in the stereo field. However, big bass is much harder to locate. Stereo bass, or bass that is too wide, generally creates problems. Use an imaging tool to make it mono, or simply create it using a mono instrument track. Many soft synths offer a width control or a stereo wheel that you can turn all the way to mono. Many electronic producers set everything below 100Hz to mono using an imager like Ozone Imager on the master track, ensuring that no rogue bass floats around in the stereo field.

Producing your mono bass with too much reverb creates a relatively big and wide sound by spreading your mono source. While some techniques can fatten up your bass and enhance its presence, improperly applying them can quickly ruin your track’s mono components. Excessive reverb or chorus on a bass will smudge other sounds in the mix and lead to phase cancellation.

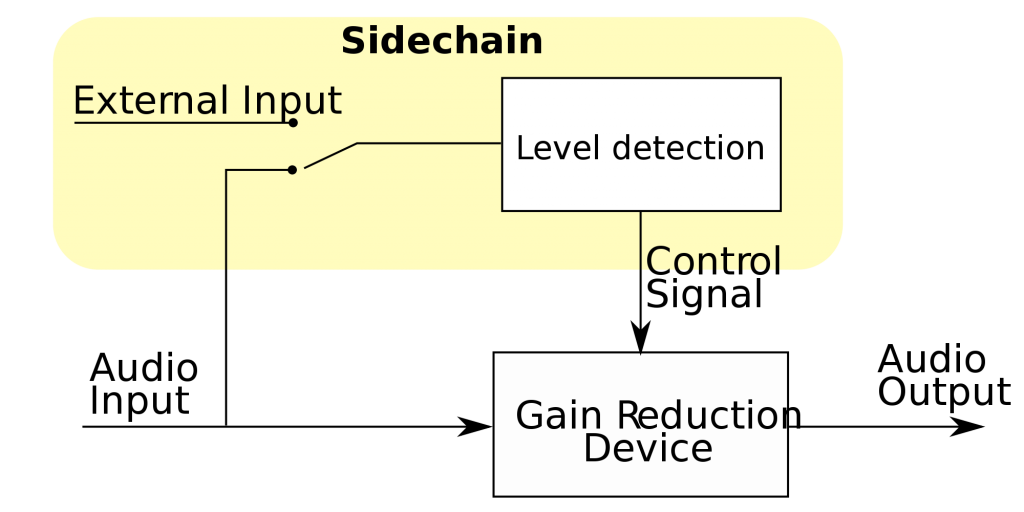

3. Sidechaining: Mixing Bass Alongside Your Kicks

Sidechaining plays a vital role in electronic music, helping you glue big kicks to big basses without phase and other issues. When you reach the stage of mixing bass in your track, ensure you have your side-chain compressor ready! When a big kick hits a big synth, it produces an enormous transient of bass energy, which can negatively affect your whole mix. Sidechaining, or ducking, provides the solution by allowing your kick to trigger a compressor on your bass track, which ducks the bass signal and lets the kick punch through effectively. This technique will assist you in mixing bass alongside your kicks.

After the kick punches through, the compressor releases, pulling your bassline back in. This process is useful and creates a great rhythmic pumping effect for your bassline. Although sidechaining might take a while to perfect, it isn’t difficult—first, route a send into the key input on your chosen compressor (this input allows you to trigger a compressor with an external signal), and then tick the side-chain box. Set the attack to trigger the compressor quickly enough after the signal enters and adjust the release to pull the bassline back in after the inputted signal drops. A higher ratio will cause greater gain reduction and ultimately result in pumping.

Conclusion

In summary, mastering the art of bass guitar mixing is essential for achieving a powerful and balanced low-end in your tracks. By focusing on clearing out unnecessary low frequencies, ensuring your bass is mono, and effectively utilizing sidechaining techniques, you can create a polished sound that enhances the overall energy of your music. Remember that each mix is unique, so take the time to experiment with these techniques to find what works best for your specific style and sound. With practice and attention to detail, you’ll be well on your way to achieving that perfect low-end that drives your music forward.

Sobre el autor

Sam Jeans

Músico, Productor y Redactor de ContenidosSam Jeans es músico, productor e ingeniero de audio. En su breve colaboración con MasteringBOX ha escrito varios artículos interesantes.

Deja un comentario

Inicia sesión para comentar