Mixing with EQ properly and effectively is a dark art, and knowing how to use EQ correctly, when, and on which instrument is one of the hardest aspects of balancing a mix to make it sound as good as possible. EQ is one of the two fundamental tools used to make a recording sound livelier and more musical, alongside compression. Other elements like reverb and spatial effects are also very important. Before diving into those, though, knowing how to use EQ in your mix will be your first step toward achieving the best results. Here is an in-depth guide on types of EQ and their individual functions so you can prepare yourself for mixing with EQ.

Table of Contents

- Mixing With EQ Properly Has Many Benefits

- Kick Drum

- Snares

- Percussion And Tom-Toms

- Cymbals

- Bass Guitars

- Guitar

- Synths

- Basslines And Subs

- Brass And Woodwind

- Vocals

- Mixing With EQ: A Note On Tonal Balance

- Start Slowly And Carefully

- Conclusion

Mixing With EQ Properly Has Many Benefits

- You allow instruments to balance tonally by carving out spaces for them to coexist in the frequency spectrum. Imbalanced instruments will sound odd when played together—for example, a loud synth and guitar can’t occupy exactly the same areas of the frequency spectrum without clashing. Mixing with EQ allows you to shape the frequency spectrum in a musical way.

- You open up a lot of headroom by cutting unneeded frequencies. Bass frequencies, in particular, will consume your headroom, essentially meaning less space for other sounds. This results in a muddy, undefined mix.

- You can accentuate particular parts of a mix to make them louder, crisper, and more defined.

- EQ doesn’t benefit every situation equally. How you use EQ depends entirely on the source audio.

Kick Drum

It’s often sensible to start off with your kick tracks. Kicks are loud transients with lots of bass, and if left un-EQ’d, they’ll wreak havoc in your mix. Firstly, kicks aren’t just bass; they contain a lot of bass frequencies, some thumpy mid-frequency content, and some high-frequency content that gives a kick its airy punch. It’s best to start by high-passing around 25Hz—the sweet spot will depend on your bassline, but more often than not, having kick information below this point is relatively inaudible and occupies a lot of headroom. Mixing with EQ to remove excessive low-end is tempting, but try not to thin out your kick too much.

Some kicks really need that high-end to help them punch through a mix. If you have a lot of frequency information from pads and percussion sitting in that same zone, that top-end will become somewhat lost. If you don’t need it, you can low-pass a kick around 2-4kHz.

The mid-frequency part of a kick around 200-250Hz is commonly referred to as ‘muddy’—these frequencies aren’t always that useful and are neither bassy nor punchy, so you can often cut in this area.

Snares

Snares, in particular, usually require mixing with EQ alongside other techniques to place them properly in the mix. A snare is a complex transient sound. It contains a lot of body in the mids and a lot of high-end, all occurring in a fraction of a second. Once again, tonal balance is needed, and we can often hone in on resonant frequencies that lie between 1-5kHz in order to eliminate some ring. If we then move down, we can often cut around 100Hz comprehensively to get rid of unneeded low-mids and bass. A notch around 400Hz can help balance your high-frequency cut.

Percussion And Tom-Toms

Drums, percussion, and cymbals are complex in their frequency content. Often, there are plenty of mid and high frequencies coming from toms, room mics, and cymbals, which include a lot of transient sounds. Learning how to mix with EQ on your drums together will take time, but it’s really worth it to reveal their details while preventing them from clashing. Mixing whole percussion tracks or drum kits takes time to master and depends on how your material was recorded. Here’s an excellent guide on recording big drums from the outset.

Cymbals

Cymbals have plenty of content around 12-16kHz that keeps them sparkly and fizzy. It’s surprising how much bass can build up from percussion tracks or buses that feel decidedly high-end, though. Often, low-passing as much as you can is an easy way to keep them from clashing with pads and synths that sit in the mids. You wouldn’t want to take too much out, though, as this could make them scratchy and very thin. Sometimes, there are buildups in the super-high frequency part of a mix above 16-18kHz, too. These are caused by stacking cymbals and percussion along with additional noise introduced from some plugins. Some like to just cut everything below 18kHz—anything above that isn’t audible to everyone and can often be unpleasant.

Bass Guitars

It’s a similar story with bass, but be careful and concentrate more on tonal shaping than cutting large areas of a bass’s frequencies. This means using a spectrum analyzer to see where exactly your kick and bass guitars intersect so you can slightly notch your bass guitar track in that area. Mixing with EQ on the bass guitar depends on the high-end snappiness or the low-end bass you need for your mix. Boost the lows for more thud and boost the upper-middle frequencies for more snap and string volume. For more info, check this article on 3 steps to mix bass.

Guitar

Mixing guitars is often intricate and a focal point of the mix. Not only that, but many mixes contain rhythm and lead parts. It can all get very tricky if you don’t know how to use EQ on your guitars carefully from the start.

Firstly, no guitar should need bass information unless it’s a solo part or part of an acoustic song, and even then, frequencies below 90Hz are seldom required. Cut them out first, and then look at the 2kHz – 4kHz zone. This area dictates how much ‘shred’ your guitar has—the meaty area to which our ear is particularly sensitive. Boost it, and you gain emphasis, but too much will sound pretty horrible. Anything above 10kHz is hard to treat—remove too much to dull and tighten your guitar sound, and your guitar will lose presence in the high notes.

Mixing with EQ on your guitar needs to be carried out in the context of your mix. Don’t do it in solo mode.

Synths

Pads and synth sounds primarily target the mid-range. They often produce thick sounds with texture, impact, and a natural size and loudness. However, a very large pad sound that lacks EQ control can smother your drums. These sounds often contain low-end content that most music doesn’t need since kicks and bass occupy that range. High-passing around 250Hz, or higher at about 350Hz, proves beneficial. Check the timbre of your pad or synth; if it sounds like you’ve shifted the pitch of the sound, you may have removed too many low harmonics. This is where tonal balancing becomes crucial, and mastering it is one of the hardest challenges—more on that later.

In a nutshell, you need to refer back to your full mix and evaluate how your pad and synth fit in terms of tone, timbre, and pitch. If cutting low frequencies makes the sound appear too high in pitch, you should make a counter cut in the high-end or upper-middle frequencies. This action balances your equalization, effectively balancing the harmonics. If you cut too much high-end and the sound feels too low in the mix, you will need to cut some low end to compensate. Mixing with EQ revolves around finding the sweet spots—if you end up with a mishmash of numerous small cuts and boosts, it may be best to start again.

Basslines And Subs

Basslines are tricky—do you cut the midrange to stop your kick from losing its thud? Do you leave mid and high frequencies in your bassline to maintain its presence? It’s a hard one…

Firstly, it’s a good idea to drop ultra-low frequency content below 30Hz. Most sound systems don’t accurately produce much volume below this frequency, so it takes up more room in your DAW than is useful. Of course, some sound systems can handle it, and cinema sound systems make good use of this zone, but in music, it’s seldom needed. Many basslines have a thick and fuzzy area around 200-250Hz, and much like a kick, it can often be cut with beneficial results. Knowing how to use EQ on a bassline or sub will keep your low-end clean and clear when it’s pumped out of a sound system. Once again, when mixing with EQ on a bassline, it’s difficult to know how much low end to remove to clean it up. Usually, just concentrate on removing information below 30Hz.

When it comes to mixing subs and bass lines, EQ along with sidechain compression will yield the best results.

Brass And Woodwind

Brass and woodwind instruments can create huge sounds that are loud and impactful. Think about the sax solo in Baker Street, for which Raphael Ravenscroft famously received £27—it’s such a memorable riff.

Brass and woodwind have tremendous warmth, with some boost in the 200Hz – 400Hz region in single mic recordings to bring it out. If you’re using multiple mics, then this isn’t always necessary, though, as the warmth and body will be captured sufficiently. Of course, the type of woodwind or brass instrument greatly affects how to use EQ! There is never a one-size-fits-all EQ set-up.

Vocals

Arguably one of the most tonally complex elements of any mix is its vocals. Recording vocals is also tricky and will change the sound depending on the microphone and positioning. Short vocal samples are obviously EQ’d differently to a full choir but the challenges remain similar as vocals sound unnatural quickly if they aren’t EQ’d properly. Knowing how to use EQ for vocal tracks depends on their focus. Are they for ambiance or do they drive the song?

Start with a high-pass filter. Anything below 60Hz rarely benefits a vocal track. Some vocals can sound harsh, so treating the area around 2.5kHz to 4kHz serves as a good starting point to reduce this harshness. Often, compensating for this cut with a boost to frequencies above 6kHz can achieve brightness without introducing harshness.

Cutting in the 1 – 2kHz zone smooths out the mix and removes vague mid-high frequencies. Finally, if you have a song that demands a very loud, large vocal part, boosting the bass from 200Hz to 600Hz injects energy into your vocal section.

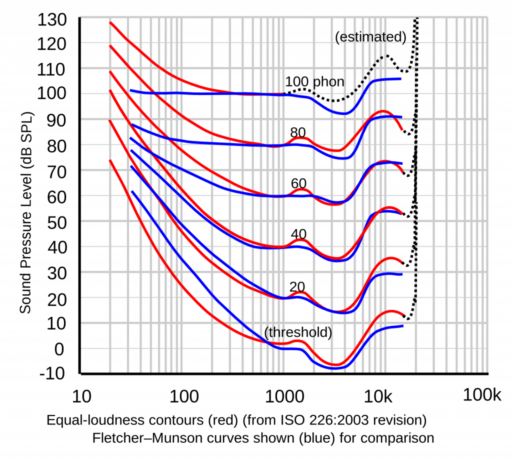

Most instruments occupy the middle or high part of the frequency spectrum. Our voice resides around 2kHz – 4kHz, making this area particularly sensitive for us. The mid frequencies extending up to that range constitute an extremely important part of the mix. A mix featuring full and controlled mid-frequency content will sound warm and full. Note in the diagram below that this region requires less volume to appear as loud to us; we are more sensitive to it, so it sounds louder.

Mixing With EQ: A Note On Tonal Balance

Balancing EQs is difficult and you’ll need to listen carefully to your whole mix every time you make a change. You can’t just cut tons and tons of low-end from everything to free up head-room as your high-end will begin to sound thin and cluttered. Avoiding mixing mistakes, including EQ issues like this, is important. At the same time, cutting too much high-end from kicks and pads will dull your mix down and remove some of its presence. It’s between these interlinking factors that mix engineers find themselves spending a long time listening to a mix. The overlap between different instruments and their complex frequency ranges is tremendous! EQ is a heavily researched area of music production, there are hugely complex guides to it like this one on SoundonSound, if you want to delve into some serious audio physics.

Start Slowly And Carefully

If you add too many frequencies around the 2 kHz area to push some brightness into percussion, the sound begins to thin out, becoming tinnier and harsher. You then compensate by adding some 100Hz to warm things back up, but you find that your mid frequencies disappear between the two boosts. Finally, when you boost around 500Hz, the sound resembles how it started but feels a bit imbalanced and unnatural. This situation highlights how not knowing how to use EQ can lead to disastrous results. You cannot simply add and add to compensate for problems or deficiencies; the same applies to subtraction. When you cut above 10kHz to remove harshness, the sound becomes too bassy, so you cut below 200Hz, resulting in an overly mid-high sound—then what do you do? You find yourself stuck!

Conclusion

If you find yourself in a situation where you’ve EQ’d many elements and everything sounds a bit off, just bypass or remove them all and start again. Follow these tips and remember: removing frequencies slowly and carefully usually yields the best results!

Sobre el autor

Sam Jeans

Músico, Productor y Redactor de ContenidosSam Jeans es músico, productor e ingeniero de audio. En su breve colaboración con MasteringBOX ha escrito varios artículos interesantes.

Deja un comentario

Inicia sesión para comentar